Japanese Ikebana - The Beautiful Art of Flower Arranging

Image courtesy of IkebanabyJunko.com

Many appreciate the innate beauty and elegance of Japanese design. But fewer have been exposed to one of its most exquisite traditions, Japanese Ikebana.

Japanese Ikebana is arranging flowers as a form of art, following traditions of Buddhism. It is more about beauty, balance and mindfulness than interior décor or accessorising the home.

As so often with Japanese design, there is much more to it than just the initial beauty, and its deceptively simple initial appearance is full of complex subtleties and deeper meaning.

In common with many of Japan’s influences on Western living, Ikebana has elegance of line, cleanness of shape and attention to colour.

Our selection of exquisite examples of Japanese Ikebana provide pleasure to the eye. Through the accompanying words, we also give newcomers a glimpse into how to appreciate this art form at other levels.

Jump to a section:

What is Ikebana?

Japanese Ikebana is the art of flower arranging, but so much more than setting blooms in a vase to please the eye. What “so much more” means may initially seem abstract, but is very rewarding to understand.

First and foremost, it is an art form. But it’s art from living materials – branches, leaves, grasses and of course flowers. And as we’ll see below, one other important “material” is empty space.

Japanese Ikebana is also about bringing nature and humanity together. An intriguing consequence of that is that both the creator and the observer of an Ikebana arrangement are in a way part of the art.

Ikebana is not just about sticking flowers into a vase: it is about the love and need of an artist to create beautiful forms . . . Ikebana is not just about the flowers, it is about the person who arranges them

Sculptural Arrangement courtesy of Ohara School of Ikebana

More prosaically, it is intended to create works of great beauty, so is subject to “rules” that define it. One might think this constrains it. But as with most art, much of the beauty comes from expressing creative freedom within and around its rules.

There are many rules in Japanese Ikebana, and much debate over the years on their details and interpretation. This has led to different forms of the art, known as “schools”. Later on, you can read about some of them, and how they've taken forward Ikebana.

Before that, you can read about the concepts and influences behind the Japanese Ikebana, adding a dimension to how you see and appreciate it.

First, take a look at our gallery of some of the best examples of Japanese Ikebana in the world.

Jump to a section:

21 Breathtaking Ikebana Creations

We contacted exponents of the Ikenobo, Ohara and Sogetsu schools of Ikebana in preparing this article.

Each school has its own own views and history, and each represents a different style of the art. But of the two thousand or so we know of, we feel these 3 are the most representative of today’s wide spectrum of Ikebana art and spirit. After the gallery we’ll tell you a little more about each school, as each has a distinguished and impressive history.

All three generously allowed us to use images of their creations, to show you what outstanding Ikebana should look like. We are grateful to our new friends for taking the time to help us, and providing these stunning samples of Ikebana at its best.

7 Ikenobo School Arrangements

Junko Kikuchi is a Professor from the Ikenobo Ikebano School. Now based in London, she is also past president of Ikebana International’s London Chapter, and was generous in sharing her time and experience. Our Ikenobo images are courtesy of Junko-san, and you can see more of her skilful work at www.IkebanabyJunko.com

You can read more about the Ikenobo School of Ikebana in the later section on Japanese Ikebana schools.

Image of Ikebana arrangement courtesy of www.ikebanabyjunko.com

Ikebana image courtesy of www.ikebanabyjunko.com

Ikenobo Ikebana by Junko courtesy of www.ikebanabyjunko.com

Ikenobe arrangement courtesy of www.ikebanabyjunko.com

Ikenobe arrangement courtesy of www.ikebanabyjunko.com

Beautiful arrangement by Ikenobo Professor Junko, from www.ikebanabyjunko.com

7 Ohara School Arrangements

Toshiko Tatsumi is from the International Division of the Ohara School of Ikebana, in Tokyo, and as with everyone else who helped with this article, it was a pleasure working with her.

You can read more about the Ohara School of Ikebana in the later section on Japanese Ikebana schools.

Rimpa form of Ohara Ikebana courtesy of Ohara School of Ikebana

Landscape Moribana arrangement courtesy of Ohara School ("Realistic" Method)

Another stunning Landscape Moribana arrangement courtesy of the Ohara School

Example of Colourscheme Moribana from the Ohara School, using the "Traditional" method

Another Colourscheme example of Moribana Ikebana from the Ohara School

Classic Rimpa arrangement from the Ohara School, inspired by Rimpa art

Bunjin arrangement of Ohara Ikebana, known for its poetic nature

7 Sogetsu School Arrangements

Finally, Hanako Katayama from the Sogetsu Foundation was as helpful and supportive as everyone we contacted, helping us with wonderful samples of work from the School’s Head, Akane Teshigahara.

You can read more about the Sogetsu Foundation in the later section on Japanese Ikebana schools.

Sogetsu arrangement of Snowball Vibrunum and Bishop's Weed in a ceramic vase

A Sogetsu arrangement featuring the fun of the vessel, with Calla and Bishop's weed

This Sogetsu arrangement features the masculinity of pine in a unique glass vase, contrasted with softer glory lilies.

Sogetsu arrangement of Thunberg spirea and flowering cherry in an iron vase, with yellow fennel adding lightness.

Sogetsu using 4 kinds of colourful tomatoes with Allium giganteum, balanced with curves of thick and thin wire.

Sogetsu arrangement of Apples and Unshiu Oranges in water coloured by stem-fluids of allium giganteum.

Boldly arranged Poinsettia, with colours and lines from soft coral and Blackboy, and lightness from a glass vase.

Jump to a section:

How to Appreciate Japanese Ikebana

Like many other forms of art, the more you understand about what the artist is trying to achieve, and the skills involved in the creation, the deeper the appreciation of what is in front of you.

The dilemma with Japanese Ikebana is that there is a lot to understand, and many different views on what’s most important, what each aspect means and even whose view matters most.

Our goal here is to give you enough knowledge to start to appreciate the Ikebana gallery below. For that, here’s our personal distillation of what we think matters most to appreciate the beauty of the Ikebana art beyond the superficial.

Freedom Through Structure

The less floral Hanamai form of Ohara Ikebana

Ikebana is a disciplined art form that has rules designed to capture the beauty of the flower arrangement. You can read about some of the most important ones later on, but for now all you really need to know to appreciate the art is that the rules exist and are complex. For example, the length of the stems relative to each other and the vase; the angles between key elements of the composition; the combinations and numbers of leaves and petals, and many more. (If you’re interested in recreational maths, you’ll like the fact that the “Golden Ratio” makes an appearance in the rules)

But the most important feature of the rules for us is that they are designed to liberate the creativity of the artist, by providing freedom within (and around) the rules. This comes across as a sense of movement or poetry, and an impression of peace and harmony through balance and colour.

It’s perhaps a strange concept, because two opposing concepts of discipline and creative expression are put together. But there are analogies, for example Haiku, the Japanese poetry form that captures the essence of a subject in a rigid construct of 17 syllables over 3 lines.

If you take another look at the gallery, you may not be able to discern any specific rules in each Japanese Ikebana arrangement. But you may well sense some of the similarities across pieces; and within those similarities, interpretation and creativity in the differences.

Representing Heaven, Earth & Human

These rules of Japanese Ikebana started out being quite rigid, but over the years different exponents of the art have evolved and even relaxed them to create many different “schools” of Ikebana.

Heaven, Earth and Human clear to see here

One of the constants across all the major schools of Ikebana is the concept of three main stems, representing Heaven, Earth and Human. Some add other stems, many use different names reflecting their view of nature, but virtually all build each piece around these 3 stems.

The concept’s origins are not certain, but it’s generally agreed that it reflects ancient Buddhist beliefs. One view is that the universe consists of Heaven above, Earth below, connected by Human between. Hence, the Heaven stem is always the tallest, Earth the shortest, and Human of middle length. Some schools even bend stems deliberately, deforming them carefully to be closer to their spiritual role.

Another interpretation we like very much is the belief that Heaven is a metaphor for the freedom and artistic aspect of the arrangement. Earth then is the metaphor for the rules that ground the arrangement, and Human is again what ties Heaven & Earth together.

Balance Through Asymmetry

While balance and harmony are key to Japanese Ikebana, unlike Western floral design it eschews symmetry. Instead, the lack of symmetry is a distinct feature, carefully created to avoid any sense of disturbance.

This is partly a more accurate reflection of nature than a stereotypical picture of a flower. By contrast, Western eyes can perceive or prefer “false” symmetry when creating a picture or arrangement of flowers.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is more to this in Japanese Ikebana than a simple absence of symmetry. There are degrees of asymmetry, and some people ascribe different levels of maturity or even spirituality to different forms of asymmetry.

This is also seen in different styles of Chinese calligraphy, where it is referred to as “shin-gyo-so”. Each name is derived from a different style of calligraphy, from block-like to highly cursive. Some Ikebana schools use these for different purposes, for example using one type of asymmetry in formal or tranquil spaces, another in dynamic settings.

Asymmetry and balance beautifully demonstrated

Ma – the Value of Empty Space

Empty space enhances this Sogetsu arrangement

Hand in hand with line, shape and asymmetry is the final key “structural” feature of Ikebana – empty space.

The Japanese concept of beauty considers space as a significant, active component, something to be designed into art and appreciated.

“Ma” means an interval of space or time, or is perhaps better translated as emptiness or void. But it’s an emptiness full of meaning, and is often positioned as a focal point of an Ikebana arrangement.

This concept of shaping a design with “negative” space is an important part of Ikebana. So arrangers may design a piece of space into the structure, framed by the flowers, leaves or stems – perhaps even subordinating them in favour of the empty element.

It’s also about the combination and interplay of space and plant. Ma allows for a sense of movement and the ability of each flower to “breathe” within the arrangement, perhaps even alluding to movement from of a non-existent breeze. There is a common belief that absence of space can lead to clutter and a lack of harmony.

The Essence of the Flower Is More than the Bloom

The importance of leaves and stem, by Junko

The word Ikebana can be translated in different ways, and one meaning is “giving life to flowers”. This is apt because an important aspect of appreciating the material is acknowledging that it’s living, and recreating that in the art.

Individual petals and leaves are chosen with care, and the flowers are handled and prepared to enhance the sense of life as well as beauty. To achieve this, the artist must understand the life cycles of the flowers, and how this affects appearance within the rules of Ikebana.

Unlike Western flower arrangements, Japanese Ikebana places emphasis on the flower as a whole, not just the coloured bloom. In an art form which values line and balance as much as colour and shape, the stalk and leaves are as important as petals.

It's also about more than just seeing what's there - part of the skill is knowing how to uncover the beauty, perhaps by removing leaves or offshoots to see it, or switching the intended angle of view.

Colour Combinations Provided by Nature

Another Colourscheme example of Moribana Ikebana from the Ohara School

Ikebana doesn’t require complex understanding of principles of colour theory. Instead it focuses on getting the arranger to understand and appreciate colours as nature combines them.

By focusing on how the flowers and plants appear in their natural habitats, the arranger is provided with an effortless set of colour combinations. Arguably, working against these would be at odds with the other principles and concepts of the art form.

Having said that, this is a good example of how new schools of Japanese Ikebana evolve. There may well be a school we’re unaware of that has rejected this concept of natural colours, instead valuing the creation of alternative colour palettes as one of the artist's contributions. We don’t know of any, but if one existed, it would fit the history of the art perfectly.

Regardless of what the colours are, or even where they come from, the colour combinations in Japanese Ikebana are intended to provide and reinforce a sense of peace and harmony – for creator and observer.

The Spiritual Connection Between Art and Artist

We’ve briefly mentioned Ikebana’s Buddhist roots earlier, and the importance of nature, heaven and the universe. But that doesn’t do justice to the importance of spirituality to this work for many.

The concept of the 3 stems representing Heaven, Earth and Human is key. Buddhist writing elaborates the importance of this further:

Man is precious only because he is part of all creation between Heaven and Earth

But the spiritual element is more than just the representation, it’s a major part of how artist experiences art during its creation, and to a lesser extent how the viewer experiences it when observing it.

At its simplest, it’s about following the Ikebana International’s suggestion of how to approach the practice of Japanese Ikebana: “One becomes quiet when one practises ikebana. It helps you to live "in the moment" and to appreciate things in nature that previously had seemed insignificant.”

This is amplified by most instructions on how to approach the designing and cutting. These all cite the need to be still, and look carefully with a quiet mind, to fully appreciate the material and its potential.

Perhaps surprisingly, we found one of the best articulations of this in Make:, the American craft magazine.

Before you begin your arrangement, look at the flowers for inspiration. Their form might suggest a season, a landscape, or a haiku. Finding this direction and letting the form of the blossom or stem guide you is the key to learning ikebana.

Don’t get caught up in the flowers themselves; rather, let your mind flow with the feelings that your branches and flowers evoke.

Jump to a section:

Ikebana Today:

Different Schools, Different Philosophies

Different schools and styles of Japanese Ikebana have developed over the years, each with their own reason for their chosen direction.

Of the 2,000 or more schools we’re aware of, we have selected three of the most well known, Ikenobo, Ohara and Sogetsu. As well as being highly respected schools, each represents a very different example of the evolution of Ikebana.

Each is led by an Iemoto (loosely translated as Headmaster or Grand Master), who follows generations of predecessors responsible for guiding, nurturing and evolving these institutions.

Ikebana is art, that is based on design or structural rules that vary between different Ikebana schools.

However, rather like vocabulary and grammar, it is the fusion of the two, the creative and rules that leads to the most accomplished artistic outcomes.

Ikenobo

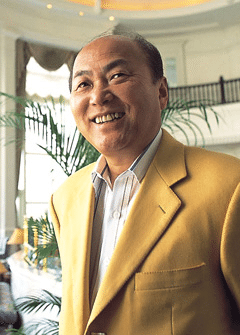

Senei Ikenobo, 45th Generation Iemoto/Head

It is generally accepted that most of the important elements of Ikebana came together over the Japanese Muromachi period in the 14th and 15th centuries. One of the most influential names in that early formative period was Senkei Ikenobo, from the Rokkaku-do Temple in Kyoto. The Ikenobo School is today based next to that temple.

Ikenobo is the family name for successive generations of the priests heading the school. The name comes from “Ike” means Pond and “Bo”, priest’s hut, and the school is currently headed by 45th generation Ikenobo family priest Sen’ei Ikenobo.

In keeping with its historic role in Ikebana, Ikenobo is known for its preservation of tradition and a reference for authenticity.

However, since the 1950s Ikenobo has been consciously adapting to the needs of current generations and new audiences. Sen’ei Ikenobo has introduced two modern variations of classic Ikebana styles, as well as encouraging the greater flexibility found in “freestyle” Ikebana.

Ikenobo is widely represented internationally, with chapters across North and South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Middle East.

Ohara

Fifth Iemoto/Head Hiroki Ohara

From its earliest days, Ikebana tended to be “vertical” in orientation, and the rules around the three main stems maintained that.

As styles evolved and schools appeared, the examples of upright designs changed, from relatively simple Tatebana “standing arrangement” to the more complex Rikka composition.

But it wasn’t until 1897 that the first style was created using “piled up flowers”. This style, Moribana, also allowed Ikebana to lend itself to the use of Western plants for the first time.

Moribana style was created by Unshin Ohara, who founded the Ohara School in 1912, just 4 years before his demise.

While all Ikebana schools emphasise the importance of Nature, it can be argued that Ohara has greater focus on Nature than many. This is because Unshin was seeking to develop a style specifically to express the beauty of natural scenery, which he spent many hours exploring.

This aim was diligently followed by the Second Headmaster Koun Ohara, and of course the subsequent three. This has led to a worldwide community of over one million students.

Sogetsu

Fourth Iemoto/Head Akane Teshigahara

Sogetsu is an almost radical contrast to the Ikenobo tradition of discipline and Ohara purpose of bringing out the beauty of nature.

The slogan of Sogetsu is “Anytime, anywhere, by anyone”, and sums up the intent behind nearly 90 years of development.

The school was conceived in 1927 by Sofu Teshigahara, with the concept of accessibility at its heart. His aim was to enable anyone to enjoy first steps into Ikebana, without limiting the skill required at the highest levels.

The emphasis on freedom of expression goes deep into the school’s culture. This shows in the artwork as “lightness”, modern feel and occasionally even humour.

It also shows in other anecdotes and features of the school. For example, the curious but successful idea of Ikebana lessons on NHK radio in the 1930s, or the dual career of Hiroshi Teshigahara as successful movie and stage director who became third Iemoto.

Akane Teshigahara is the current Iemoto/Head, and embodies the school’s artistic tradition. She describes herself as being brought up in an artistic environment, and explains that she cherishes “free creation”.

Jump to a section:

The End, and Perhaps a Beginning

Discovering Ikebana has been a pleasurable eye-opener for all of us here at Zayah World. We've long admired Japanese art and design from a distance and enjoyed visiting the country.

But we've never looked as closely at the art as we needed to for this article, and it's been a revelation. In particular, our biggest learning has been the way the art touches so many aspects of life if allowed to.

As with the Tibetan Mandala we wrote about recently, this art form is best appreciated by slowing down and really looking carefully - perhaps not just with your eyes. Our experience has been that the more you look, the more you see.

And given how much there is to see, we felt the most appropriate way to close is with something Junko Kikuchi told us, after 30 years of studying Ikebana:

Ikebana is a lifelong journey pursuit of perfection.

If expertise is perfection, then to become an expert requires a lifetime of pursuit, with the goal never quite reached.